The house is full of arnica*,And mystery profound;

We do not dare to run about

Or make the slightest sound;

We leave the big piano shut

And do not strike a note;

The doctor’s been here seven times

Since father rode the goat.

He joined the Lodge a week ago—

Got in at four A.M.,

And sixteen Brethren brought him home,

Though he says that he brought them.

His wrist was sprained and one big rip

Had rent his Sunday coat—

There must have been a lively time

When Father rode the goat.

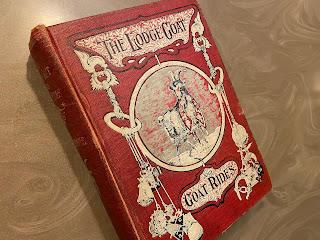

—“When Father Rode the Goat”, from The Lodge Goat and Goat Rides by James Pettibone (1909)* — Arnica is a plant with yellow flowers that was commonly used to treat bruises.

At some point in our Masonic lives, most of us have heard brethren joking with nervous candidates about a “lodge goat” tied up out back for later in the evening. We’re told over the years that these jokes are inappropriate, that there’s no such thing as a “lodge goat,” and that the stories about Masons riding goats in their initiations are just myths. So, when first-time visitors explore the Masonic Library and Museum of Indiana, many are startled to round a corner and come face to face with a large, horned, furry billy goat. At several times throughout the history of the Grand Lodge of Indiana, various grand masters and grand secretaries have issued stern warnings to lodges, admonishing brethren to never joke about the solemn degree ceremonies, specifically warning against making goat jokes. And yet, here sits a prime specimen of the Capra hircus on the 5th floor of the Grand Lodge building (albeit an artificial, wheeled, mechanical critter of the species).

So, is our ‘Billy’ proof that the Masons really do “ride the goat” in their ceremonies?! Well, not exactly.

The public has always had a fascination with the secret initiation rites of fraternal societies like the Freemasons, the International Order of Odd Fellows, the Knights of Pythias, the Rosicrucians, the Red Men, and many others, and goat lore has been attached to the “Secret Orders” from the very start. Interestingly, the word caper, meaning “a playful or slightly questionable activity” actually comes from the Latin root capra, the word meaning “nanny goat.”

The eminent 19th-century English Masonic historians George Oliver and Robert Freke Gould traced the origin of Masonic goat tales back to the Middle Ages when bearded rams were seen as symbolic of the devil himself. Legends were told of witches who called forth Satan, riding into town on a he-goat to take part in their blasphemous orgies, and witches were often depicted riding goats themselves. Early anti-Masons accused Masons of deviltry (when that meant actually dealing with the Devil, and before the term evolved to more commonly mean just childish mischievousness), and the goat-riding tales quickly got shifted from witches to Masons.

The Golden Age of Fraternalism, from the end of the American Civil War up through the 1929 Great Depression, exploded with new fraternal groups and secret orders. In an article in the North American Review from 1897, the writer H. S. Harwood reported that fraternal groups claimed five and a half million members, out of a total adult U.S. population of about nineteen million. Four out of every ten American men belonged to at least one of more than 1,000 different “secret societies”, all competing for their hearts, minds, participation, and membership dues. Truly obsessive and enthusiastic fraternalists could attend a different lodge meeting every single night of the month, and every group had their own pseudo-esoteric initiation ritual that usually used classical, literary, or Biblical symbolism to teach lessons about morality, charity, honesty, and more. Some were more serious than others, but with so many groups a typical lodge meeting consisted of reading the minutes from the previous month, paying the bills, maybe enjoying a pitch-in dinner, followed by a hot hand of euchre. And so, to attract more members, newer groups began to invent decidedly un-serious initiation ceremonies. And on occasion, they could get quite raucous. Initiation rumors about the “Secret Orders” became so widespread during this period that it was only a matter of time before some group really would add a goat to their meetings.

The Modern Woodmen of America was founded in 1883 by Joseph Cullen Root specifically to offer insurance benefits to its members. In 1894, their ritual book introduced a new ceremony they called the “Fraternal Degree.” The ritual specified that the hoodwinked initiate be placed on the back of a mechanical goat and bounced around the “hall three or four times, care being taken not to be too rough.” Their official history, written in 1924, stated, “there was an immediate increase in interest in the work of our 'Camps' (i.e. lodges) and a corresponding impetus to growth resulted.”

The DeMoulin Brothers in Greenville, Illinois were already manufacturing furniture, costumes, props, and other paraphernalia for fraternal lodges by 1890, and they weren’t alone. They had lots of competition around the country to satisfy the needs of literally thousands of lodges, but the DeMoulin boys began specializing in building elaborate props for hazing new initiates, and their business skyrocketed. Products included exploding altars, collapsing chairs, electrified carpets, butt-paddling machines, trick guillotines, life-sized skeleton marionettes, water-squirting devices of all kinds, and, of course, mechanical goats. As you can imagine, college fraternities also became eager customers for the DeMoulins.

At their height, they offered at least five different models of bucking goats, with optional accessories like electrified stirrups and water-squirting collars: The Bucking Goat; the Lowdown Buck; the Fuzzy Wonder; the Rollicking Mustang Goat; and the Ferris Wheel Coaster Goat. The business became so lucrative that, around Greenville, their plant became known as “the goat factory.”

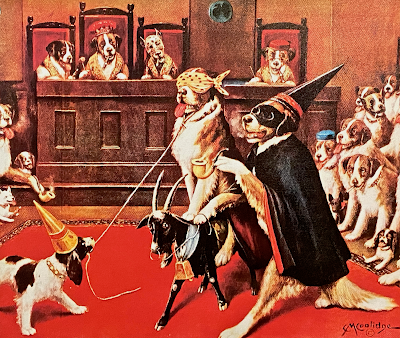

Lodge goats also appeared in pop culture during this period. In 1900, American artist Cassius Marcellus Coolidge, best known for his “dogs playing poker” painting, created one print in his famous dog series that showed a fraternal lodge filled with canines initiating a hoodwinked St. Bernard, led with a cable-tow around his neck by a cocker spaniel, and riding on the back of a goat.

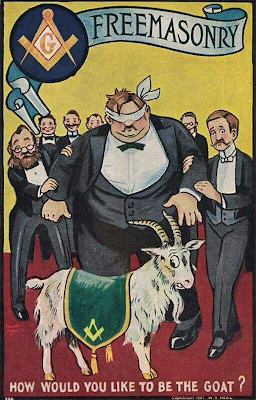

In 1916, a short, silent animated cartoon featuring a popular bad-boy character named Bobby Bumps was released, about a young prankster attempting to trick his best friend Mose into being blindfolded and butted in the backside by a barnyard goat. And over the years, many novelty postcard companies offered up collections of “lodge goat” cartoons, showing Masons or other fraternal members with a tipsy goat among their group, drinking toasts, butting candidates, acting as the lodge Tyler, and more.

Our particular billy goat at the Masonic Library & Museum of Indiana is a DeMoulin Brothers’ Model 188 “Bucking Goat.” Its metal wheels are mounted deliberately off-kilter to provide a more wobbly ride for the poor unsuspecting initiate, and the push handle in the rear allowed the tormenting operator to make the goat wildly pitch back and forth. Such a critter was never permitted for use in any Masonic degree ceremonies, and ours actually came from a former Odd Fellows lodge in southern Indiana. But that didn’t stop plenty of fraternal lodges from creating clubs and unauthorized “inner orders” that made up side degrees specifically to make use of these kinds of hazing devices.

If lodge members weren’t especially gifted at inventing their own ceremonies, the DeMoulins helpfully sold playbooks with various scenarios and recommendations for more effectively humiliating or scaring the hell out of candidates in order to enliven meetings, raise charity money, and delight the audience. Of course, the whole point of all these raucous, hazing hijinks was that, after a new initiate had successfully withstood the humiliation from his Brethren, his greatest desire as the newest member of the lodge was to inflict the same treatment – or even worse – on the next poor, blind candidate who knocked on the door.

Alas, the demand for goats and guillotines in fraternal lodges has long since fizzled out, but the DeMoulins are actually still in business today, specializing in band uniforms. They have their own very fun and unique museum in Greenville, Illinois displaying their wilder products from the fraternal past, including a selection of their bucking billies. It’s well worth a visit.

He’s resting on the couch today

And practicing his signs

The hailing signs, working grip,

And other monkey-shines

He mutters passwords ’neath his breath

And other things he’ll quote;

They surely had an evening’s work

When father rode the goat.

i have a De Moulin collapsing stair. The candidate was told his initiation was over and photos would be taken. He ascended the stairs and a fake camera ignited exploding power while the stairs collapsed. Years ago a De Moulin executive visited my collection and was quite knowledgable about the use of collapsing stairs and the varieties.

ReplyDeleteThis is not funny, and it makes a joke out of very serious matters.

ReplyDelete